1) Describe how ADF’s order of ritual expresses the following concepts: “Serving the people”; “Reaffirming shared beliefs”; “Reestablishing the cosmic order”; “Building enthusiasm”. (Min. 500 words)

ADF’s order of ritual expresses “serving the people”:

When discussing how the folk are served in ADF ritual, it is important to acknowledge that not all celebrants are looking for the same thing when they enter a ritual space, nor are the purposes of all rituals the same. Bonewits discusses how various age groupings of people may come to and enjoy a ritual for varying reasons. A teen and a senior are likely not expecting to get the same thing out of ritual, and so serving each of them exclusively would look different (Bonewits 66-70). Corrigan highlights some of the many purposes of ritual, which range from season celebrant to rites of passage (Corrigan “Intentions”).

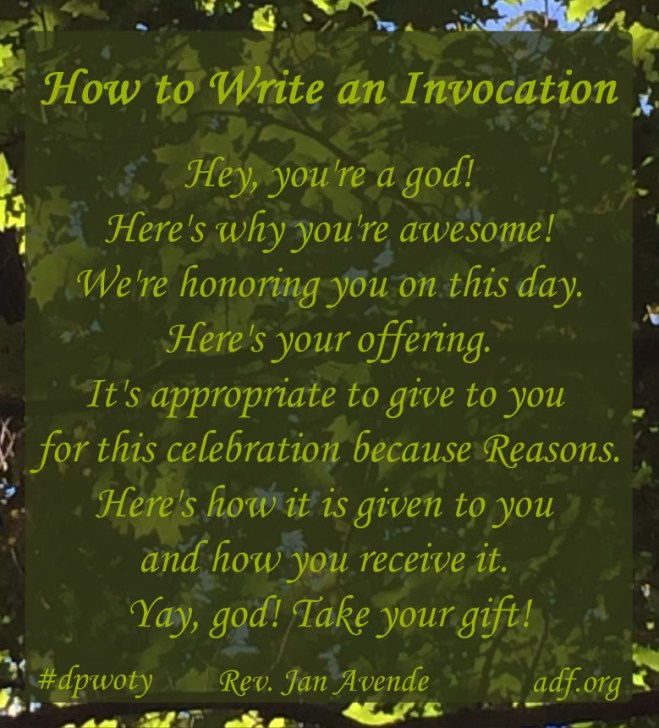

In general however, the folk are served in ritual as their connection with the Kindreds is deepened. This is done throughout the ritual as we engage in acts of sacrifice and *ghosti. Offerings are made to each of the Kindreds in turn as they are invited (“ADF COoR” Step 7), and then, during the Return Flow (“ADF COoR” Step 11-13), gifts are given back to the folk. In our local rituals, the folk are always given an opportunity to bring forth their own offerings of praise to the Kindreds, which I think helps to further deepen the connection that each individual can feel with the spirits. This personal offering can also make the blessing received during the Return Flow more personal as well. Each individual is more likely and more able to take the Omen and the Blessing within themselves as they connect to the spirits.

ADF’s order of ritual expresses “reaffirming shared beliefs”:

As an orthopraxic, rather than orthodoxic, religion, our shared beliefs are perhaps more understated and less necessary than the shared practices of our ritual. Beliefs that we are likely to share are reaffirmed through our expression and practice of them. For example, we revere the Earth, and this belief is reaffirmed through our practice of honoring her first and last in the core order of ritual (“ADF COoR” Step 3). We believe in the concept of reciprocity, and this belief is reaffirmed through the act of making sacrifices and partaking of the Return Flow (“ADF COoR” Step 11-13). Reaffirming shared beliefs can also occur during the pre-ritual briefing, though this is not an official step of the core order of ritual. This allows the people leading the ritual a time to briefly explain things such as the worldview and mythological setting that the ritual will be occurring in, and to field any questions that folks may have to that everyone is on the same page going in to the ritual (Bonewits 59-60).

ADF’s order of ritual expresses “reestablishing the cosmic order”:

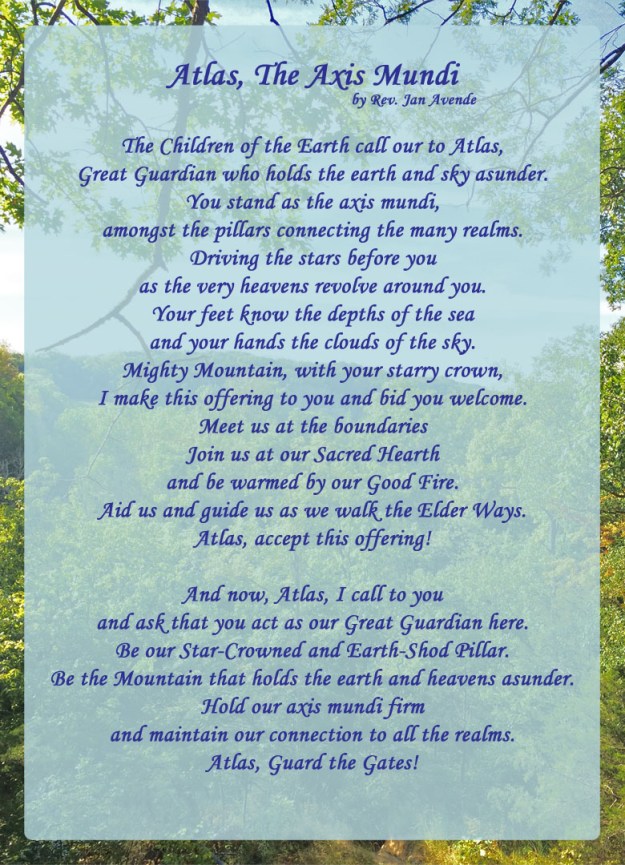

The purpose of reestablishing the cosmic order is to provide an orientation for our ritual and to help “orient the ritual participants in relation to all the other parts of their universe and to all the other beings in it” (Bonewits 31). This is done rather explicitly in the core order of ritual where the cosmos is (re)created with the Sacred Center situated in a triadic cosmos where the Three Realms are acknowledged and the Fire is included (“ADF COoR” Step 5). In this way an axis mundi is established connecting the vertical realms (the Lower Realm, the Mid Realm, and the Upper Realm) as well as a horizontal division of the realms, often the land, sea, and sky.

I find it most effective to first find the Center within ourselves. This is often done by acknowledging the Outdwellers and purifying and preparing ourselves for ritual (“ADF COoR” Step 2). Then find the Center within the group. This is where the Two Powers meditation comes into play, allowing the participants to establish a group mind (“ADF COoR” Step 1) where they connect to the Waters deep in the earth and the Fire high in the sky, becoming their own axis mundi. Then finally establishing the Sacred Center of the Worlds where the ritual will take place and making sacrifice as we (Re)Create the Cosmos and order the world (“ADF COoR” Step 5).

ADF’s order of ritual expresses “Building enthusiasm”:

We build enthusiasm in our ritual when we raise energy through the ritual performance. This often begins by calling to a power of inspiration to fill us, such as the Awen, the Muses, or Soma, and it is often the person filling the role of Bard who has a large part in maintain the flow of energy and enthusiasm (“ADF COoR” Step 1). Enthusiasm can translate to mana, or energy, or power. The Bard keeps the energy level high, keeps the folk focused, and the power steady and building throughout the ritual until it comes to the point to use it for something, whether that is taking the Blessings into ourselves or performing a working.

The enthusiasm continues to build as the Gates are opened (“ADF COoR” Step 6) and the connection to the powers deepens. As each of the Kindreds are called, and sacrifices are made, more enthusiasm is generated (“ADF COoR” Step 7). “Mana stimulates mana — the more you generate, the more you attract, and vice versa” (Bonewits 139). While there are many ways of generating mana, one of the most common we see in ADF rituals is sacrifice, as we make offerings through the ritual. The power and enthusiasm continues to build in waves as more songs are sung, chants are chanted, and sacrifices are made up through the Final Sacrifice (“ADF COoR” Step 9), when it can be sent as part of this offering. Following this the energy we are gifted in return is taken into ourselves for the work that is to come.

2) Create a prayer of praise, offering, or thanksgiving to a deity modeled on a mythic, folkloric, or other literary source of at least 75 words. Include a summary of what your sources were and how you utilized them (summary at least 150 words).

“Ushas, Shining Dawn”

O, Daughter of the Sky, dancing in the light arising from darkness

I stand entranced by your beauty,

Your radiant form laying across my mind just as it drapes across the sky.

Rosy gold droplets stream down your freshly bathed limbs, bright and beautiful maid,

As you waken the pious spirits to sing your hymns.

Rekindling my heart just as you rekindle Agni each new day.

Burning hot and strong in me, just as you do on earth.

I court you, O brilliant maiden, as you shower me with your riches,

Singing praises with my voice just as the sky itself sings colors for you.

Breath and life of all, awaken all to motion as you dance across the rim of the world.

Goddess of the ever-rising sun, glowing in radiant splendor,

Never far from my thoughts, never far from me.

Ushas, Bright greetings of the morning!

I have had a growing interest in the Vedic deities, and have always loved the dawn. This led me to begin reading from the Rig Veda the many hymns to Ushas, the Vedic Goddess of the Dawn. One of the things I’ve found most interesting about the Vedic deities in general is that they do not represent the things of their domain, but rather they simply are the things of their domain, similar to the Titans and earlier deities in Greek mythology. For example: Agni is the Fire, Soma is the juice of Inspiration, and Ushas is the Dawn.

I read the hymns that mentioned Ushas in the Rig Veda, both silently and aloud. I must throw in an aside here: always, always read hymns aloud. This is how they were meant to be conveyed, and there is a certain power held within the words that is released when they are spoken. Some of the things I noticed in particular in the structure of the Vedic hymns is the use of repetition and parallel structure. Ushas is often addressed as “Ushas”, “Daughter of the Sky,” “Lady of the Light,” with “O” often beginning these phrases. This makes the whole hymn seem more regal, and while perhaps simply a product of the translation, it is common across most of the Vedic hymns. The structure of the many of the hymns to Ushas set up to describe her, and then tell what she does, and then describe her some more, and then tell more of what she does. The hymns then often end with a petition, asking her to give something to those who are signing her praises. These aspects of the original hymns are what I kept in mind as I wrote mine: the regal use of her name and her titles, the descriptions of what she looks like, telling what she does, and in this instance a greeting to her rather than a direct petition for something from her. I’ve included a list below of some of the specific imagery that that I’ve pulled from the Rig Veda in writing my own hymn to her.

I addition to reading about her, mostly straight out of the Rig Veda, I spoke with others who have worked with her, and I wrote a lot. I filled pages and pages of my bardic notebook describing her, praising her, exploring her facets, and courting her. I spent pages detailing how she looked on a clear morning, and even more pages on how she looked as she forced the clouds to parts to make way for the sun. I wrote excessively on all the colors she displayed as she arose, and lamented the mornings where the fog was too thick to see her clearly, writing about those as well. I spent a lot of time both in exploring how my view of her reflects and matches the view of her in the Rig Veda, but also how to phrase the hymn so that it carried aspects of the style of the hymns in the Rig Veda.

Here are the hymns I referenced when writing this prayer (Griffith), as well as what imagery or phrasing I used from it:

RV I.48 (O Daughter of the Sky, breath and life of all, answer our songs of praise with your brilliant light)

RV I.113 (Agni being rekindled, breath and life of all)

RV I.123 (resplendent, always appearing at the appointed time and place: rta)

RV IV.51 (awaken the pious)

RV V.79 (use of repetition, O Daughter of the Sky,

RV V.80 (freshly bathed limbs, rta)

RV VI.64 (arising from the waters dripping, rta)

RV VI.65 (waken pious spirits, rta)

RV VII.77 (stirring all life to motion)

RV VII.78 (rekindling Agni and the fire-priests, Daughter of the Sky, inspired with thoughts of you)

RV VII.79 (painting the Sky with her colors)

RV VII.80 (awaken pious spirits and the fire-priests to sing her praises, turns our thoughts to fire and sun and worship)

RV VII.81 (O Daughter of the Sky, giver of wealth)

3) Discuss a poem of at least eight lines as to its use of poetic elements (as defined by Watkins): formulaics, metrics, and stylistics. Pay particular attention to use of meter and phonetic devices, such as rhyme and alliteration. (Minimum 100 words beyond the poem itself.)

“Do not go gentle into that good night”

by Dylan Thomas

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Formulaics is the use of repetitive words and phrases across languages. These are common phrases that have the same meaning, as well as the same root, morphology, and syntax. They are especially common in Vedic and Greek poetry, and the closer a language is to the common proto-language, the more instances of common phrases across the languages occur (Watkins 12-16). The use of formulas was extremely useful for ancient poets, because it gave them phrases to gather and use when orally reciting and embellishing their text, and allowed the work itself to focus on a particular theme or themes. This meant that the oral tradition was in part so successful in this time piece due to the phrases that were well-recognized and used through many of the works of the time (Watkins 16-19).

“Do not go gentle into that good night” is a villanelle, which means that it follows a strict formula in the repetition of its lines as well as its rhyme scheme. A villanelle is a 19 line poem that uses the first and third lines of the first stanza alternating as the last line of each remaining stanza, until the final stanza where they form a rhyming couplet. The repeating lines in this poem are “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” (Thomas 3, 7). Thomas also juxtaposes throughout the poem with these lines the idea of light and dark, death and life. As these lines repeat they emphasize the theme of the poem, which is to fight against the end of life and continue living with passion until your last breath.

Metrics is how stressed and unstressed syllables combine to form words, lines, and phrases. Ancient poetry was often isosyllabic and if lines were longer would often contain a caesura in the middle of the line near the 5th syllable. Poems analyzed with metrics are often viewed by looking at the chunks of syllables based on where the breaks in the line are, meaning both the caesura and the end of the line. The formulas that are used often conform to these syllabic boundaries (Watkins 19-21).

“Do not go gentle into this good night” is written in iambic pentameter, which is notated as [10 -] (except for line 14, which is 11 syllables, and notated as [11 -]) and divided into five tercets followed by a quatrain (Watkins 123-4). Each stanza explains a thought: the first introduces the idea of living until your last breath and fighting against dying; the second through fifth stanzas each give an example of the type of men that fight against death; and the sixth stanza (the quatrain) implores the speakers father to be as those men described and fight against his death (Thomas). Additionally, the strong meter creates a rhythmic quality to the poem, making it feel more like a call to arms, and really augmenting the “rage, rage” imperative of the poem.

Stylistics are all the other poetic elements that are examined when analyzing texts. This includes things like alliteration, parallel structure, assonance and consonance, rhyme, repetition, simile, metaphor, among others. Alliteration was one of the most common poetic elements that ancient poets across many Indo-European cultures employed, and was often used as an embellishment to the text (Watkins 21-25).

The rhyme scheme of a villanelle is a strict ABA, ABA, ABA, ABA, ABA, ABAA. Thomas makes extensive use of repetitive sounds using alliteration, assonance, and consonance. Each of these devices emphasizes words in the text to highlight their meaning as it relates to the overall theme of the piece. Some examples of alliteration in the poem are “Go Gentle..Good” (1), “Learn…Late” (7), and “ Sang…Sun” (10) Some examples of assonance are “Age…rAve…dAy…rAge…agAInst” (2, 3) and “dEEds…grEEn” (8). An example of consonance is “bLinding…bLind…bLaze” (13, 14).

4) Create a prayer suitable for the main offering of a High Day rite which includes invocation of at least one deity suitable to the occasion, description of the offering and its suitability to the occasion, and the purpose of the offering, totaling at least 100 words. Any stage directions necessary for performance of the offering should be included.

This invocation was made at Three Cranes Grove’s Summer Solstice ritual in 2014, celebrating Prometheia and honoring Prometheus as the deity of the occasion.

Prometheus, flame-haired Foresight and friend of mankind

The Children of the Earth call out to you!

Sculpting our flesh from the banks of the sacred River Styx

You made us: Children of the Earth and starry Sky.

You see the future, and know what may come.

You stole the Divine Fire, the Sun itself,

Giving us this gift of Fire, knowing the cost to you.

Through you we know the ways of the land,

We gather together as community, bound together by your gift,

Though this gift yet binds you to the Earth.

The Fire, burning light of the Stars, burning light of the Sun,

Meant only for the Gods.

You won it for us, your Children.

Your fiery spirit burns hot and strong,

sharing its heat with us here on Earth.

Flame-haired trickster, and Mighty Titan.

Your wisdom shines brightly down upon us

As the Sun rides high in the Sky today.

Prometheus, you who sacrificed for us

So that we may sacrifice for you and all the Gods.

We call out to know and honor you this day!

Come, be warmed at our Fire, that we have kept burning for you,

Join us at our Sacred Hearth, that we would not have if not for you,

Meet us here at this time when the Fire is strongest,

And continue to aid and guide us as we walk the Elder Ways.

We bring you sweet oil *hold aloft*, for your Fire to drink in.

Prometheus, Fiery Titan,

Accept our Sacrifice!

*pour oil on the fire*

Works Cited

“The ADF Core Order of Ritual for High Days.” Ár nDraíocht Féin: A Druid Fellowship. ADF. Web. 6 Jan. 2015. < https://www.adf.org/rituals/explanations/core-order.html>.

Bonewits, Isaac. Neopagan Rites: A Guide to Creating Public Rituals That Work. Woodbury, Minn.: Llewellyn Publications, 2007. Print.

Corrigan, Ian. “The Intentions of Drudic Ritual.” Ár nDraíocht Féin: A Druid Fellowship. ADF. Web. 6 Jan. 2015. <https://www.adf.org/rituals/explanations/intentions.html>.

Griffith, Ralph T.H. Rig Veda. Sacred Texts, 1896. Web. 8 Jan. 2015. <http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/>.

Thomas, Dylan. “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets, 1937. Web. 8 Jan. 2015. <http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/do-not-go-gentle-good-night>.